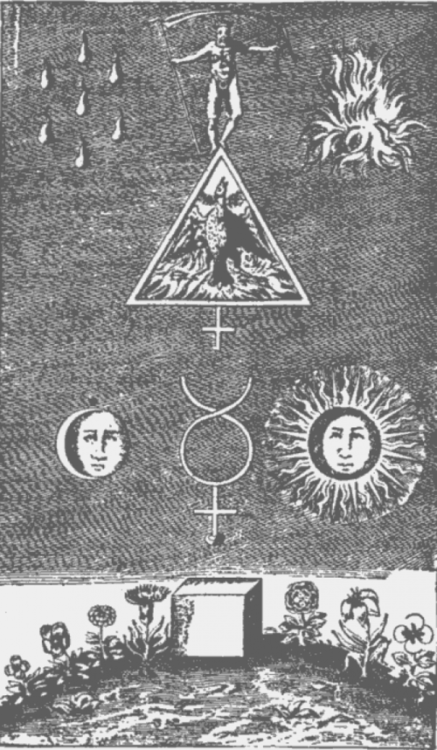

"Alchemy is a three stage work in its simplest outline...with each stage represented traditionally by a different color and set of meaningful images. In the first, the person to be enlightened is broken down, shattered really, to their core idea or ‘prime matter.’ ...The second stage is one of purification or cleansing. The shattered survivor of the [first stage] here is washed and restored in preparation for the chrysalis of the remaining stage...The last stage is red ....The end-color of the alchemical process is gold, the illumined metal or ‘solid light,’ which represents the enlightened person who has achieved something like divinization or union with the ‘Light of the World.'"

- From Unlocking 'Mockingjay': The Literary AlchemyIn a series of three stages then, the hero -like the alchemist and his base metal- is transformed from lead into gold. It's impossible to say whether the original writer or teller of the Beauty and the Beast tale intended an alchemical reading of the story. I don't think so- rather, I think the story, in all its different forms, seems to touch upon alchemical stages through similar imagery and themes. The physical and mental transformations of the characters and the wedding of opposites (we'll get to that later) makes it ripe for an alchemical retelling, and I think storytellers have picked up on that. I won't be discussing any and all versions of the tale, however. I'll just stick to three: De Villeneuve's original, Robin McKinley's Beauty, and the Disney film, Beauty and the Beast. I do so mainly because these three are a bit more popular than others and these are also the ones I have most recently read. If anybody has anything to add to the discussion about other versions, I'd be delighted. So, to begin:

The first stage that John refers to above is called the Nigredo Stage, or the Black stage. Here “the body of the impure metal, the matter for the Stone, or the old, outmoded state of being is killed, putrefied, and dissolved into the original substance of creation, the prima materia, in order that it may be renovated and reborn in a new form” (Granger quoting from Lyndy Abraham). In an alchemical story this is marked by the hero having his world shattered, or by the hero being in intense hardship. Its imagery involves darkness and (of course) the color black. Both de Villeneuve's original and Mickleny's Beauty start out in this Nigredo stage when Beauty and her family are struck by sudden misfortune. In the original tale, the family house burns down (creating black ashes), and then--in both versions--Beauty's father's luck in business drops altogether and the family goes from living a rich and luxurious lifestyle to a incredibly simple one in the country. The whole story hinges on this breakdown: Beauty and her family have been literally stripped away from the all that is unnecessary and begin "living in the simplest way" (V, 2).

The second stage is called the Albedo, or the purifying White stage. Now that the material or character has been broken done to its base material, it is now to be purified and cleansed (source). Images in this stage of an alchemical novel include water, silver, the moon, and whiteness. The most prevalent image in all three versions of the Beauty and the Beast tale is easily snow. Each version differs slightly on their treatment of snow, but in all three there is snow, snow, snow right up to the doors of Beast's castle. In the original it is "deep snow and bitter frost"(4) that prompts Beauty's father to enter the Beast's castle and its a track "presenting itself only as a smooth ribbon of white" (65) that leads the way to the castle in Beauty (In the Disney film, the father is chased by white wolves in white snow right up to the castle's gate).

However, it's the Disney film and Mckinley's Beauty that have my favorite albedo imagery. In Beauty, the Beast's castle acts as a sort of shelter from outside and there's hardly a day that goes by that's not filled with nice weather. The first time it rains, however (and remember water is an important image here) the weather prompts Beauty and the Beast to spend time together inside rather than outside. With not much else to do, the Beast introduces beauty to the library, the one place above anywhere else in the castle that eventually brings Beauty and Beast together. The library not only makes Beauty's time in the castle more enjoyable, but it also sparks a new friendship between her and the Beast. Beauty narrates, "most days after that we took turns reading to each other. Once...he did not come in one day, and I missed him sadly"(159). The library not only establishes a friendship, but a trust as well: after the Beast introduces her to his favorite books and authors, Beauty decides to introduce him to her beloved horse in return (149). In the weather- sheltered world of the castle, rain plays an important role in bringing the two characters together, in cleansing their relationship.

There are also two similar Albedo scenes in the Disney film. When Belle runs away from the castle (after going into the Beast's 'forbidden room') she mounts her horse and rides away into the thickest snowstorm yet. She is soon attacked by a pack of wolves and rides her horse deep into a frozen lake (becoming drenched with water). Barely making it out of the lake before the wolves, Belle is then saved by the Beast, who comes out from nowhere and drives the them away. This marks the first change in their relationship: the Beast saves Belle and she, instead of continuing to run away from him, brings him back to the castle and tends to his wounds. After some sideline scenes with Gaston and her father, the film then returns to Beast showing (and then giving) Belle his library. Afterwards they play like children in the snow and they become literally covered in whiteness. The whole time they do so they form new ideas about each other (highlighted by the song "There's Something There" playing in the background).

In all three versions then, the color white serves to illuminate their feelings towards one another. Snow and water play an important role in beginning and cleansing Beauty and the Beast's relationship, in bringing them closer to understanding and trusting one another.

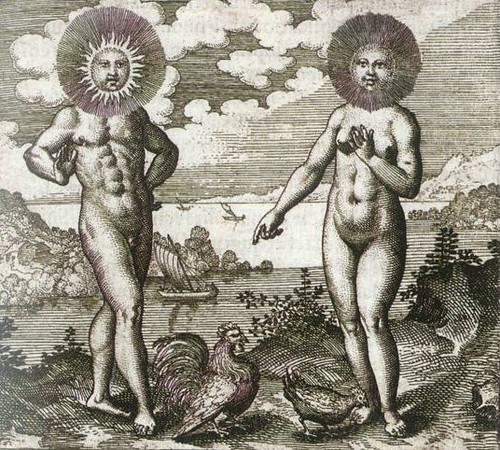

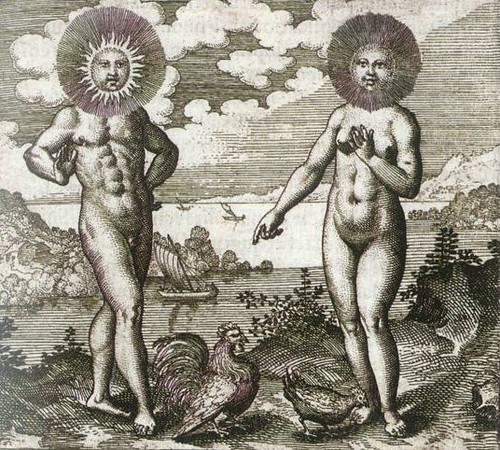

Before the last stage (which we'll get to- I promise!) it's important to know that in an alchemical framework there is what John Granger calls the"resolution of contraries," or the Alchemical Wedding. Scholar Erin N. Sweeney writes, "In alchemy the polarity of masculine and feminine is united to make a whole through a process called the alchemical wedding...the major part of the work of alchemy is the union of yin [feminine] and yang [masculine]" (Harry Potter for Nerds, 180).

Before the last stage (which we'll get to- I promise!) it's important to know that in an alchemical framework there is what John Granger calls the"resolution of contraries," or the Alchemical Wedding. Scholar Erin N. Sweeney writes, "In alchemy the polarity of masculine and feminine is united to make a whole through a process called the alchemical wedding...the major part of the work of alchemy is the union of yin [feminine] and yang [masculine]" (Harry Potter for Nerds, 180).

The very title of Beauty and the Beast tells us that this is a story about the coming together of two opposites. Any and all versions of the tale will be about the resolution of Feminine Beauty (the moon, silver, cool, wet, the Soul) and the Masculine Beast (the sun, gold, hot, the Spirit).

In a very long story made short (a story I think I'll forever be unraveling), an alchemical wedding involves the masculine spirit (the sun) passing above from within to unite with the receptive feminine soul (the moon) The spirit thus descends to to join the soul, and the soul must ascend to meet the spirit (Sweeney, 193).

I think the contraries in the Beauty and the Beast tales are obvious enough, but each version deals with it a little differently. The Disney version does a particularly wonderful job illustrating this meeting of contraries alchemically. I pull the following quote from the wonderful blog Tales of Faerie about the clothing of the characters:

*When Beast tries to eat in a more human like manner (like Belle), he can't help but make a mess. So delicate Belle meets him halfway by eating in a more animalistic way (like the Beast). Then in harmony, their bowls meet each other in the middle of the table as a sort of "cheers" (you can watch this exchange in the beginning of the 'Something There' video link posted above).

*At the end of the film, Gaston attacks Beast at the top of the castle. As Beast falls further and further down the castle turrets, Belle runs up the staircase to meet him. Bell arises and Beast descends and they meet in the middle right before the Beast's transformation and right before the third and final alchemical stage.

While its definitely most prevalent in the Disney film, the original story is not without this alchemical wedding. In alchemy the pair of opposites are also called "the quarreling couple" and though the couple in the original never outwardly argue, every night they disagree. Each time the Beast asks Beauty for her hand in marriage he is hoping for a "yes," yet she always tells the Beast a solid "no." Her final "yes" at the end of the story marks the end of the 'quarreling couple' and the beginning of their resolution.

The third stage, then, is the golden-red Rubedo stage. The matter has been broken down to its base material, has been washed and purified. The contraries have been married and the material is ready to be perfected, to be transformed into gold. Unsurprisingly, this final stage of the alchemical work is signified by splendrous light and by red and golden colors.

The third stage, then, is the golden-red Rubedo stage. The matter has been broken down to its base material, has been washed and purified. The contraries have been married and the material is ready to be perfected, to be transformed into gold. Unsurprisingly, this final stage of the alchemical work is signified by splendrous light and by red and golden colors.

In the original, when Beauty finally agrees to marry the Beast golden colors and glowing imagery abounds: "As she spoke a blaze of light sprang up before the windows of the palace; fireworks crackled and guns banged, and across the avenue of orange trees, in letters all made of fireflies, was written: Long live the prince and his bride" (25).

In Robin Mckinley's Beauty Beauty is trying to return to the Beast, but gets lost in darkness in the forest. She doesn't find him until a full day and night of riding and when she does, it is "nearly dawn" (237). Light is returning and she notices "The Beast was wearing golden velvet...instead of the dark brown I had last seen" (237). When she tells him she loves him and wants to marry him, "there was a wild explosion of light, as if the sun had burst...I was buoyed up by light and sound" (239). After the Beast has his transformation (still wearing his gold vest), Beauty looks into a "mirror with a golden frame" (242) and has a realization that she's had her own sort of transformation as well into a beautiful girl with "copper red hair" and "amber" eyes. Finally, as they leave the castle together and as the novel ends, "thousands of candles in the crystal chandeliers blazed in greeting, till they rivaled the light of the sun" (247).

The Disney film's version is also steeped in golden and light imagery. (Watch the Beast's transformation here.) There's not only falling light as the Beast transforms, but golden fireworks as the two embrace and a golden falling light that transforms the whole castle back to its more lively and purified self.

Alchemy is about transforming both an external material and one's internal self. Likewise, the Beauty and the Beast tale is never about just one transformation, but two: the Beast's external transformation and Beauty's internal one. In the end, both have been cleansed and purified. Through their relationship, both ultimately come to a deeper understanding of the world and of the transformative power of love.

Alchemy is about transforming both an external material and one's internal self. Likewise, the Beauty and the Beast tale is never about just one transformation, but two: the Beast's external transformation and Beauty's internal one. In the end, both have been cleansed and purified. Through their relationship, both ultimately come to a deeper understanding of the world and of the transformative power of love.

What do you all think? Is this a classic case of "too much analyzing" or could these storytellers (and story re-tellers) have alchemy in mind? What do you make of elements of the story I didn't go into, like the rose?

As you can probably tell, I've only just scratched the surface of describing what alchemy really does. Finding alchemical imagery is easy enough, but the rest continues to boggle my mind. While I will try my hardest to answer any question you have about alchemy, I will not pretend to be any expert in the field. Thus, while I urge you to of course leave questions and comments, I'd also have you check out the following books and websites if I have piqued your curiosity:

Anything John Granger (this is a great resource)

The original Story

Beauty by Robin Mckinley

Disney film

Dictionary of Alchemical Imagery

The second stage is called the Albedo, or the purifying White stage. Now that the material or character has been broken done to its base material, it is now to be purified and cleansed (source). Images in this stage of an alchemical novel include water, silver, the moon, and whiteness. The most prevalent image in all three versions of the Beauty and the Beast tale is easily snow. Each version differs slightly on their treatment of snow, but in all three there is snow, snow, snow right up to the doors of Beast's castle. In the original it is "deep snow and bitter frost"(4) that prompts Beauty's father to enter the Beast's castle and its a track "presenting itself only as a smooth ribbon of white" (65) that leads the way to the castle in Beauty (In the Disney film, the father is chased by white wolves in white snow right up to the castle's gate).

However, it's the Disney film and Mckinley's Beauty that have my favorite albedo imagery. In Beauty, the Beast's castle acts as a sort of shelter from outside and there's hardly a day that goes by that's not filled with nice weather. The first time it rains, however (and remember water is an important image here) the weather prompts Beauty and the Beast to spend time together inside rather than outside. With not much else to do, the Beast introduces beauty to the library, the one place above anywhere else in the castle that eventually brings Beauty and Beast together. The library not only makes Beauty's time in the castle more enjoyable, but it also sparks a new friendship between her and the Beast. Beauty narrates, "most days after that we took turns reading to each other. Once...he did not come in one day, and I missed him sadly"(159). The library not only establishes a friendship, but a trust as well: after the Beast introduces her to his favorite books and authors, Beauty decides to introduce him to her beloved horse in return (149). In the weather- sheltered world of the castle, rain plays an important role in bringing the two characters together, in cleansing their relationship.

|

| Artist |

In all three versions then, the color white serves to illuminate their feelings towards one another. Snow and water play an important role in beginning and cleansing Beauty and the Beast's relationship, in bringing them closer to understanding and trusting one another.

Before the last stage (which we'll get to- I promise!) it's important to know that in an alchemical framework there is what John Granger calls the"resolution of contraries," or the Alchemical Wedding. Scholar Erin N. Sweeney writes, "In alchemy the polarity of masculine and feminine is united to make a whole through a process called the alchemical wedding...the major part of the work of alchemy is the union of yin [feminine] and yang [masculine]" (Harry Potter for Nerds, 180).

Before the last stage (which we'll get to- I promise!) it's important to know that in an alchemical framework there is what John Granger calls the"resolution of contraries," or the Alchemical Wedding. Scholar Erin N. Sweeney writes, "In alchemy the polarity of masculine and feminine is united to make a whole through a process called the alchemical wedding...the major part of the work of alchemy is the union of yin [feminine] and yang [masculine]" (Harry Potter for Nerds, 180). The very title of Beauty and the Beast tells us that this is a story about the coming together of two opposites. Any and all versions of the tale will be about the resolution of Feminine Beauty (the moon, silver, cool, wet, the Soul) and the Masculine Beast (the sun, gold, hot, the Spirit).

In a very long story made short (a story I think I'll forever be unraveling), an alchemical wedding involves the masculine spirit (the sun) passing above from within to unite with the receptive feminine soul (the moon) The spirit thus descends to to join the soul, and the soul must ascend to meet the spirit (Sweeney, 193).

I think the contraries in the Beauty and the Beast tales are obvious enough, but each version deals with it a little differently. The Disney version does a particularly wonderful job illustrating this meeting of contraries alchemically. I pull the following quote from the wonderful blog Tales of Faerie about the clothing of the characters:

"In the words of Art Director Brian McEntee, 'Beast starts out in very dark colors; Belle starts off in very cool colors. As the film progresses, her wardrobe warms up and his cools down. When you get to the ballroom, she's in gold, and he's in blue: they're falling in love, so they're at the same place.'"If that doesn't scream alchemical wedding, I'm not sure what does. The imagery surrounding Belle goes from cool soul to warm spirit. Likewise, Beast goes from warm soul to cool spirit. There's a couple of other "meeting in the middle" imagery in the film as well:

*When Beast tries to eat in a more human like manner (like Belle), he can't help but make a mess. So delicate Belle meets him halfway by eating in a more animalistic way (like the Beast). Then in harmony, their bowls meet each other in the middle of the table as a sort of "cheers" (you can watch this exchange in the beginning of the 'Something There' video link posted above).

*At the end of the film, Gaston attacks Beast at the top of the castle. As Beast falls further and further down the castle turrets, Belle runs up the staircase to meet him. Bell arises and Beast descends and they meet in the middle right before the Beast's transformation and right before the third and final alchemical stage.

While its definitely most prevalent in the Disney film, the original story is not without this alchemical wedding. In alchemy the pair of opposites are also called "the quarreling couple" and though the couple in the original never outwardly argue, every night they disagree. Each time the Beast asks Beauty for her hand in marriage he is hoping for a "yes," yet she always tells the Beast a solid "no." Her final "yes" at the end of the story marks the end of the 'quarreling couple' and the beginning of their resolution.

The third stage, then, is the golden-red Rubedo stage. The matter has been broken down to its base material, has been washed and purified. The contraries have been married and the material is ready to be perfected, to be transformed into gold. Unsurprisingly, this final stage of the alchemical work is signified by splendrous light and by red and golden colors.

The third stage, then, is the golden-red Rubedo stage. The matter has been broken down to its base material, has been washed and purified. The contraries have been married and the material is ready to be perfected, to be transformed into gold. Unsurprisingly, this final stage of the alchemical work is signified by splendrous light and by red and golden colors.In the original, when Beauty finally agrees to marry the Beast golden colors and glowing imagery abounds: "As she spoke a blaze of light sprang up before the windows of the palace; fireworks crackled and guns banged, and across the avenue of orange trees, in letters all made of fireflies, was written: Long live the prince and his bride" (25).

In Robin Mckinley's Beauty Beauty is trying to return to the Beast, but gets lost in darkness in the forest. She doesn't find him until a full day and night of riding and when she does, it is "nearly dawn" (237). Light is returning and she notices "The Beast was wearing golden velvet...instead of the dark brown I had last seen" (237). When she tells him she loves him and wants to marry him, "there was a wild explosion of light, as if the sun had burst...I was buoyed up by light and sound" (239). After the Beast has his transformation (still wearing his gold vest), Beauty looks into a "mirror with a golden frame" (242) and has a realization that she's had her own sort of transformation as well into a beautiful girl with "copper red hair" and "amber" eyes. Finally, as they leave the castle together and as the novel ends, "thousands of candles in the crystal chandeliers blazed in greeting, till they rivaled the light of the sun" (247).

The Disney film's version is also steeped in golden and light imagery. (Watch the Beast's transformation here.) There's not only falling light as the Beast transforms, but golden fireworks as the two embrace and a golden falling light that transforms the whole castle back to its more lively and purified self.

Alchemy is about transforming both an external material and one's internal self. Likewise, the Beauty and the Beast tale is never about just one transformation, but two: the Beast's external transformation and Beauty's internal one. In the end, both have been cleansed and purified. Through their relationship, both ultimately come to a deeper understanding of the world and of the transformative power of love.

Alchemy is about transforming both an external material and one's internal self. Likewise, the Beauty and the Beast tale is never about just one transformation, but two: the Beast's external transformation and Beauty's internal one. In the end, both have been cleansed and purified. Through their relationship, both ultimately come to a deeper understanding of the world and of the transformative power of love.

* * *

As you can probably tell, I've only just scratched the surface of describing what alchemy really does. Finding alchemical imagery is easy enough, but the rest continues to boggle my mind. While I will try my hardest to answer any question you have about alchemy, I will not pretend to be any expert in the field. Thus, while I urge you to of course leave questions and comments, I'd also have you check out the following books and websites if I have piqued your curiosity:

Anything John Granger (this is a great resource)

The original Story

Beauty by Robin Mckinley

Disney film

Dictionary of Alchemical Imagery