With the theme of the conference being Invoking Wonder, Verlyn Flieger's plenary address examined the subtle ways that J.R.R. Tolkien himself invokes wonder within his Lord of the Rings, noting that the way in which he does so almost always includes a "rebound effect" in which the reader experiences wonder and awe not directly from the narrator, but by means of redirection through a character within the story. One of her most clear examples of this within The Lord of the Rings was the scene in which Frodo encounters Lórien for the first time:

"The others cast themselves down upon the fragrant grass, but Frodo stood awhile still lost in wonder. It seemed to him that he had stepped through a high window that looked on a vanished world. A light was upon it for which his language had no name. All that he saw was shapely, but the shapes seemed at once clear cut, as if they had been first conceived and drawn at the uncovering of his eyes, and ancient as if they had endured for ever. He saw no colour but those he knew, gold and white and blue and green, but they were fresh and poignant, as if he had at that moment first perceived them and made for them names new and wonderful. In winter here no heart could mourn for summer or for spring. No blemish or sickness or deformity could be seen in anything that grew upon the earth. On the land of Lórien there was no stain" (350).

Lórien, therefore, is not merely described, but experienced—and specifically experienced through Frodo. In fact, it is singularly through Frodo, as if there is a spotlight on him as he alone stands "lost in wonder" as the others take respite among the grass. In this moment of quiet and solitary wonder Frodo, as Flieger noted in her address, sees things anew: familiar colors "were fresh and poignant, as if he had at that moment first perceived them" and ordinary shapes seem "as if they had been first conceived and drawn at the uncovering of his eyes." For Frodo has been blind (and literally so, as he was until this moment blindfolded) until this raw moment of wonder when he sees things fresh and anew.

Tolkien rebounds the sense of wonder from the character to the reader so that the thought and experience of Frodo becomes our own. And, as Flieger noted, an important element in invoking this wonder is Tolkien's removal of language within the passage. Familiar and defining words are gone as the narrator states, "a light was upon it for which his language had no name." Likewise the colors Frodo sees are indefinable and new, being "as if he had at that moment perceived them and made for them names new and wonderful." In the removal of language here, Flieger noted, Tolkien makes us experience something new. We and Frodo alike are no longer grounded in familiar definitions and language. Here is a scene immeasurable in language, experienced only in thought, in wonder.

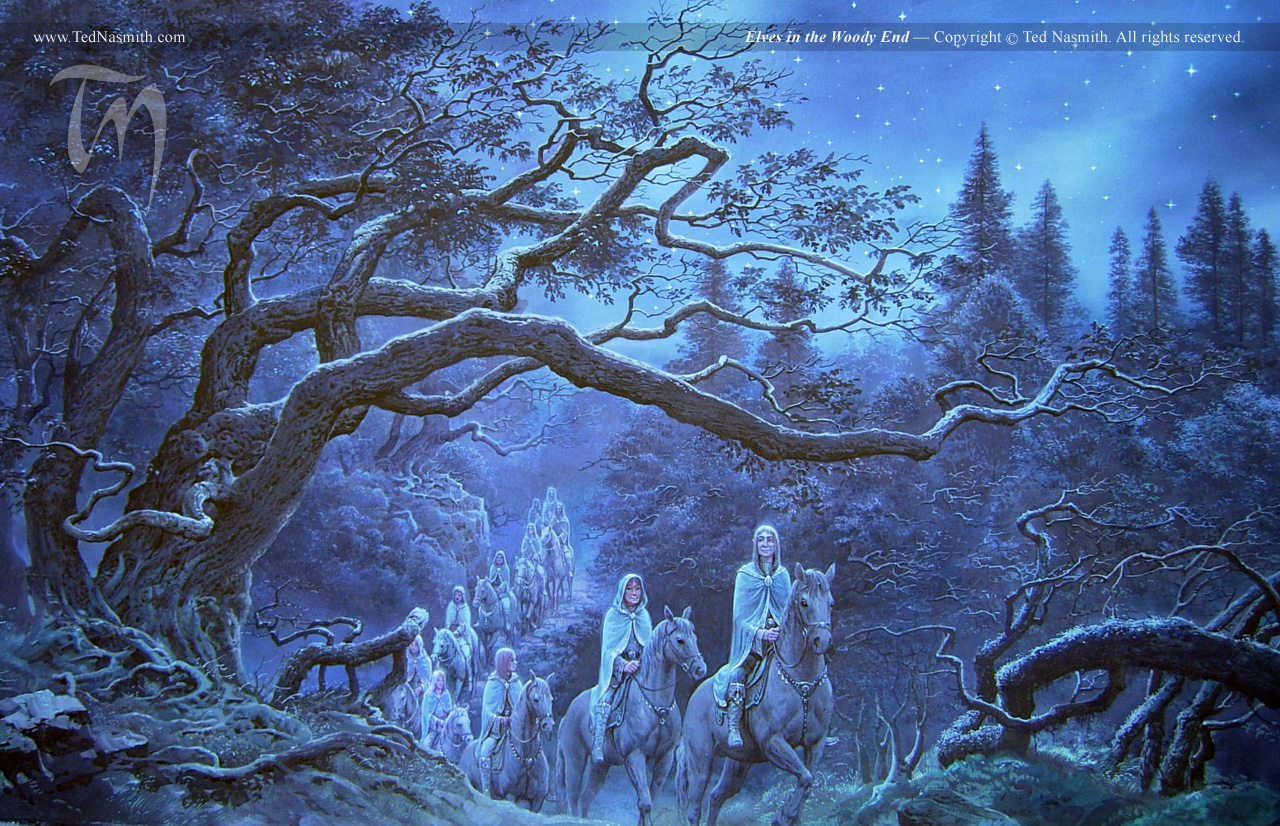

While Flieger suggests that Tolkien uses language—or rather the lack of language to invoke wonder, I would expand this to suggest that he likewise does so with storytelling and song, using Frodo and the hobbits to redirect wonder upon the reader. As he did by removing the words or language, Tolkien often removes the story from the hobbits or reader. And often true wonder is achieved best through a lack of the story rather than the story itself. While there are plenty of moments Tolkien gives us history and information (like what we see in the Shadow of the Past and histories of Gondor in later in LotR) and even songs, when it comes to the story and storytelling, a lot of the time Tolkien gives us pieces rather than the whole [1]. In On Fairy Stories Tolkien calls fantasy "the making or glimpsing of Other-worlds" (14). This idea that we experience fantasy with a glimpse of the otherworld rather than a whole view is one that is essential to Tolkien and his own fantasy. Significantly, the reader's introduction to the magic within The Lord of the Rings, for instance, is not done with an immediate and full picture of the elves. It is done with fragmented stories and glimpses, found only within the "shadowy marshes" (OFS) of Tolkien's own Perilous Realm. In The Green Dragon we learn that Sam,

"believed he had once seen an Elf in the woods, and still hoped to see more one day. Of all the legends that he had heard in his early years such fragments of tales and half-remembered stories about the Elves as the hobbits knew had always moved him most deeply" (77).

|

| Ted Nasmith |

So when we come to hear tales later on in the novel, it's no surprise that the most enchanting stories—like those fragmented tales Sam once heard—are the ones that aren't told in full. No clearer is this felt than in the House of Tom Bombadil, where wonder is invoked not through answers but by riddles. Not by fully recounted stories, but by the enchantment felt from storytelling:

"When they caught his words again they found that he had now wandered into strange regions beyond their memory and beyond their waking thought, into times when the world was wider, and the seas flowed straight to the western Shore; and still on and back Tom went singing out into ancient starlight, when only the Elf-sires were awake. Then suddenly he stopped, and they saw that he nodded as if he was falling asleep. The hobbits sat still before him, enchanted; and it seemed as if, under the spell of his words, the wind had gone, and the clouds had dried up, and the day had been withdrawn, and darkness had come from East and West, and all the sky was filled with the light of white stars. Whether the morning and evening of one day or of many days had passed Frodo could not tell. He did not feel either hungry or tired, only filled with wonder" (168).We are given no complete story here. Instead, we experience enchantment and wonder through Frodo. As readers, we are no longer being asked to believe in the truth of stories, but rather in their ability to bring us to enchantment. Tolkien does this again in Rivendell when Frodo listens to the singing of the elves:

"At first the beauty of the melodies and of the interwoven words in elven-tongues, even though he understood them little, held him in a spell, as soon as he began to attend to them. Almost it seemed that the words took shape, and visions of far lands and bright things that he had never yet imagined opened out before him; and the firelit hall became like a golden mist above seas of foam that sighed upon the margins of the world" (281).Frodo is swept away by words he doesn't understand, far lands he has never seen, and "bright things he had never yet imagined." It is in this context that we are shortly given Bilbo's song of Eärendil, a tale that is wondrous all the more for the build up in enchantment that precedes it. It's clear that the reader would not experience the same level of wonder in the songs, histories, and stories actually given (like those of Eärendil, Tinùviel, or Nimrodel) without these moments in which Tolkien leaves out a complete story or song to show us the ultimate power of storytelling and song. By doing so, Tolkien ensures that we are never become disillusioned with the magic or history within The Lord of the Rings. Even though we, like Sam, come to know and experience it, we are always guided to a new, deeper enchantment: the enchantment of a story we have never—will never—hear. There is always more, always something deeper that we cannot quite touch.

This concept extends out to the actual experience of reading the very book in our hands. Our wonder is elevated when we experience this second layer enchantment reached through storytelling within the novel itself. It reminds us of what the best literature, the best stories, can evoke. Throughout The Lord of the Rings the reader is subtly, but strongly reminded of the magic of storytelling itself, even as she takes part in reading that same story.

In his own write up about the Mythmoot IV conference fellow Mythgardian and friend Tom Hillman points to the poem Bilbo recites shortly before Frodo and the company leave Rivendell:

I sit beside the fire and think

Of all that I have seen

Of meadow flowers and butterflies

In summers that have been

Of yellow leaves and gossamer

In autumns that there were

With morning mist and silver sun

And wind upon my hair

I sit beside the fire and think

Of how the world will be

When winter comes without a spring

That I shall ever see

For still there are so many things

That I have never seen

In every wood in every spring

There is a different green

I sit beside the fire and think

Of people long ago

And people that will see a world

That I shall never know

But all the while I sit and think

Of times there were before

I listen for returning feet

And voices at the door

This poem isn't about Bilbo's grand adventures. No dragon, dwarf, gold, great mountain, or wizard makes an appearance. It has no story. And yet is clearly nonetheless about wonder. There is a clear connection between past and present: of what was, what is, and what will be. But it is equally about what never was, no longer is, and what will not be for Bilbo himself. This poem is recited just after Bilbo reflects, "I’ll do my best to finish my book before you return. I should like to write the second book, if I am spared" (333). And thus the wonder and poignancy lies within what this poem doesn't describe. Perhaps even within the story that Bilbo's book —and thus the very book in our hands—can never tell. Like the maps of Hobbiton, the enchantment lies in what's beyond the edges.

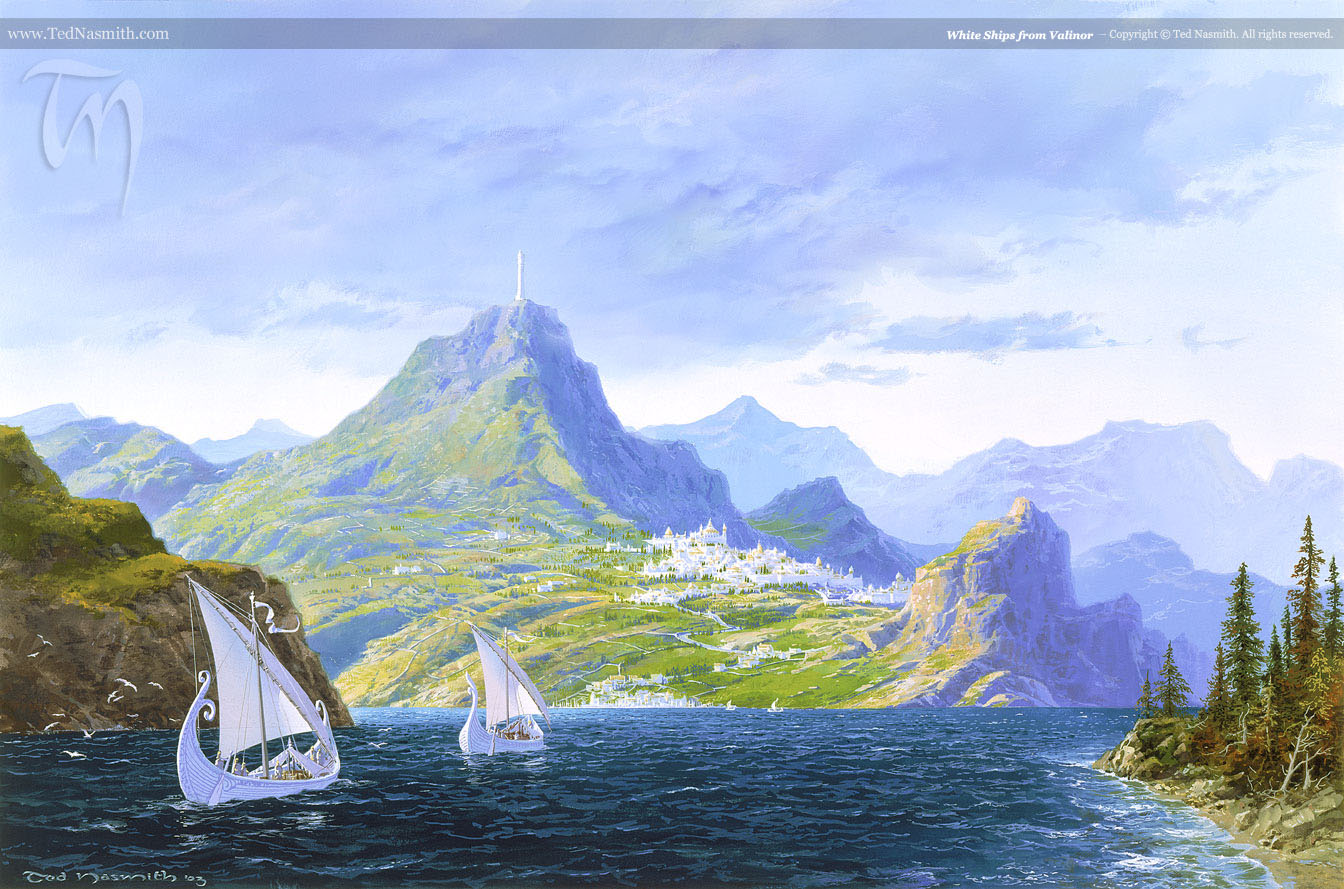

And so it is along the edges we walk. Within the "margins of the world" we touch upon greater legends, greater stories, enchanting storytelling. If we go back to the scene in Lothlórien, with Frodo standing alone in wonder and awe of the world before him, we can see that Tolkien doesn't go very far before reminding us what story and song means within his work:

Naturally, in this moment of wonder, there is no actual song. Wonder is invoked all the more clearly and strongly without one. Just as Tolkien removed the words to describe Lórien from Frodo, he likewise removes the song from Sam. And as so often is the case with Tolkien, wonder is felt most strongly in its absence. As readers we may walk along the edge, but every so often if we're lucky, we stumble into the indescribable Perilous Realm, gaining a glimpse of something new. We become part of a story that has yet to be told, a song in the making."He turned and saw that Sam was now standing beside him, looking round with a puzzled expression, and rubbing his eyes as if he was not sure that he was awake. ‘It’s sunlight and bright day, right enough,’ he said. ‘I thought that Elves were all for moon and stars: but this is more Elvish than anything I ever heard tell of. I feel as if I was inside a song, if you take my meaning’" (351).

Ted Nasmith

|

| Ted Nasmith |

[1] Meaning not of course, what was posthumously published in The Silmarillion, of which we are often given a song in LotR instead of the story in its entirety.